EU-China cultural diplomacy: room for improvement in troubled times?

By Ina Kokinova

The Beijing Olympics have just ended. This blog looks at the state of play of cultural diplomacy between the EU and the People’s Republic of China. Looking forward to the EU-China summit in April, the article emphasises the value of cultural cooperation rather than competition, despite the increasing geopolitical tensions.

A momentum until 2018?

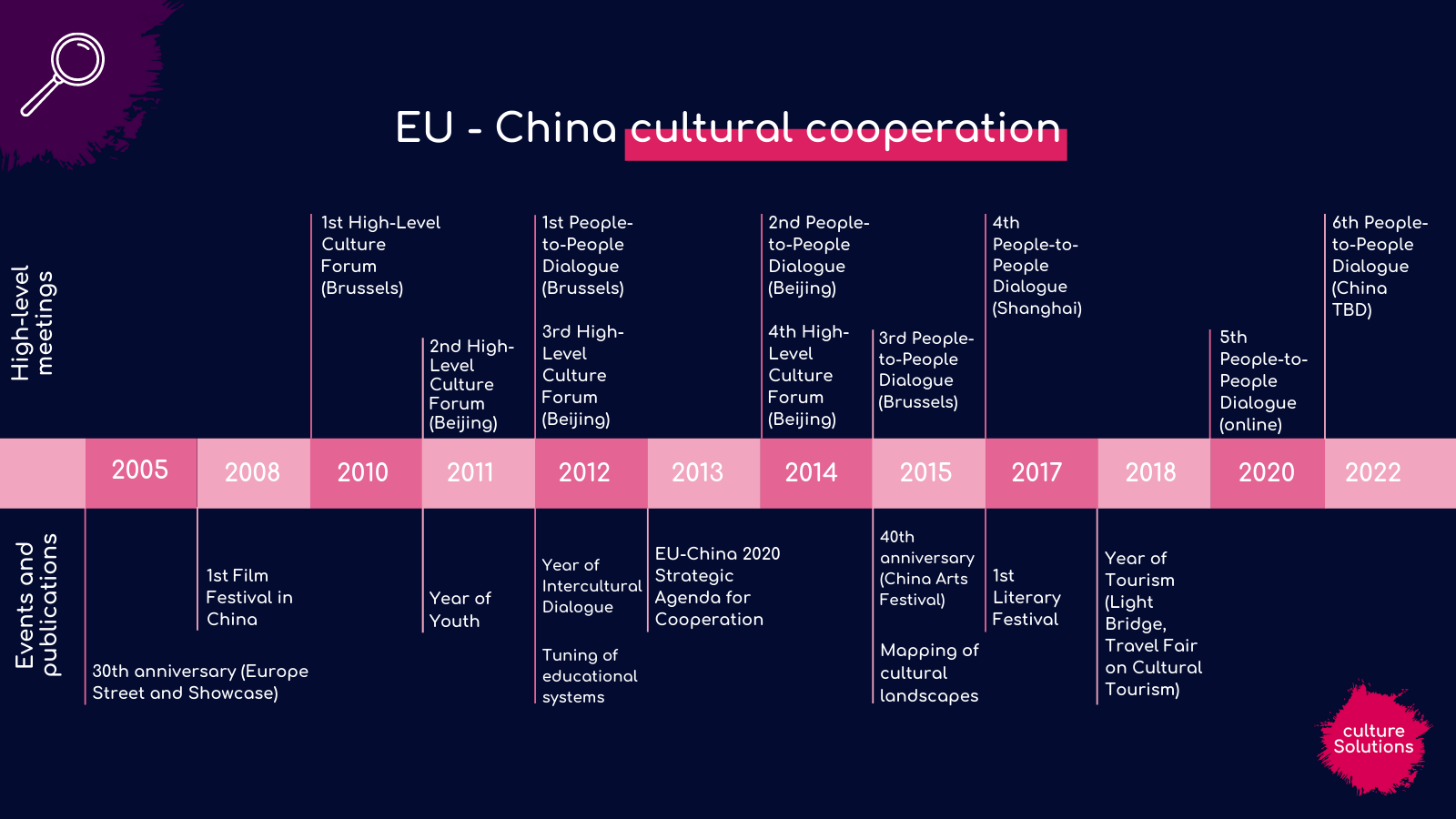

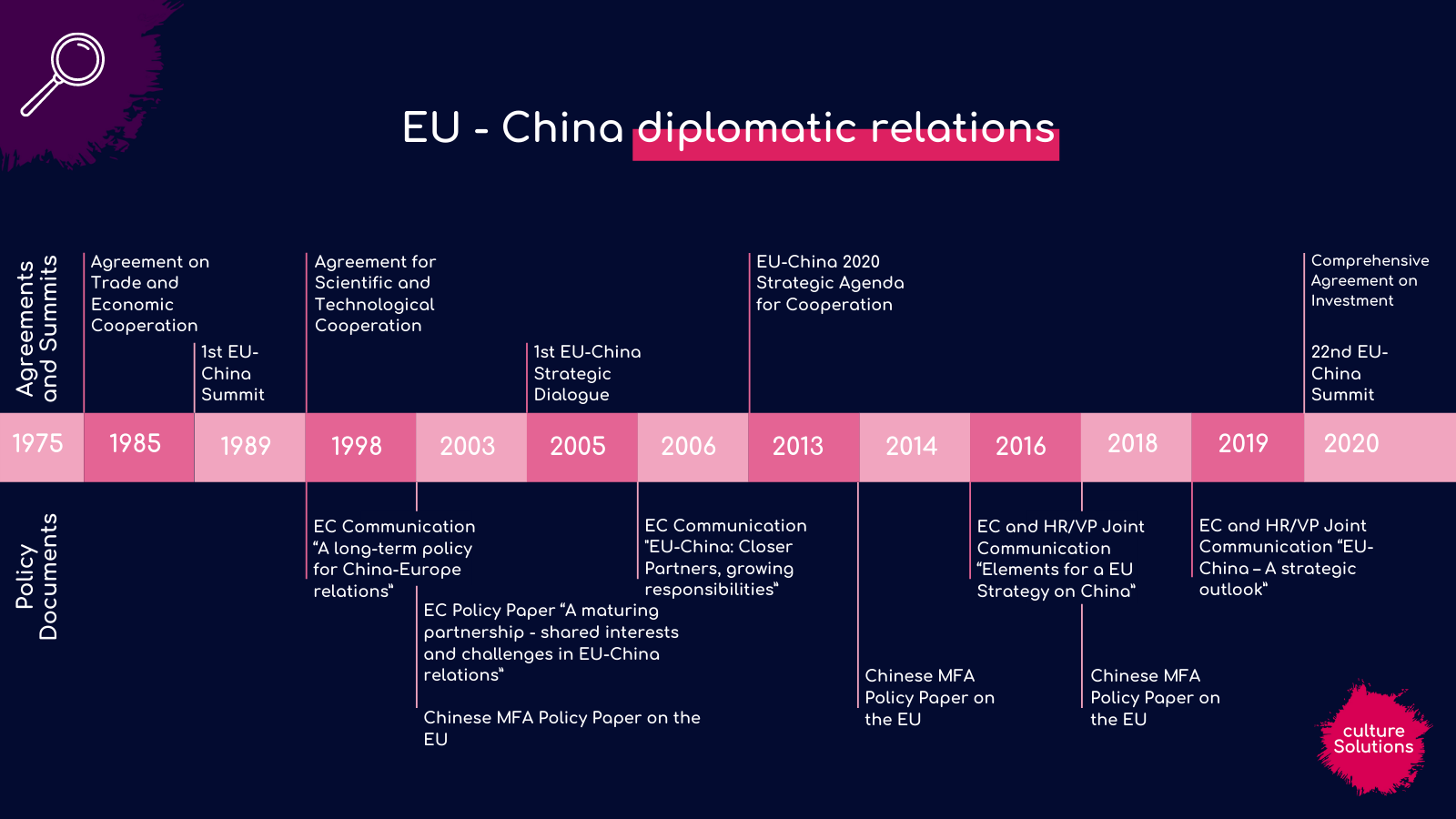

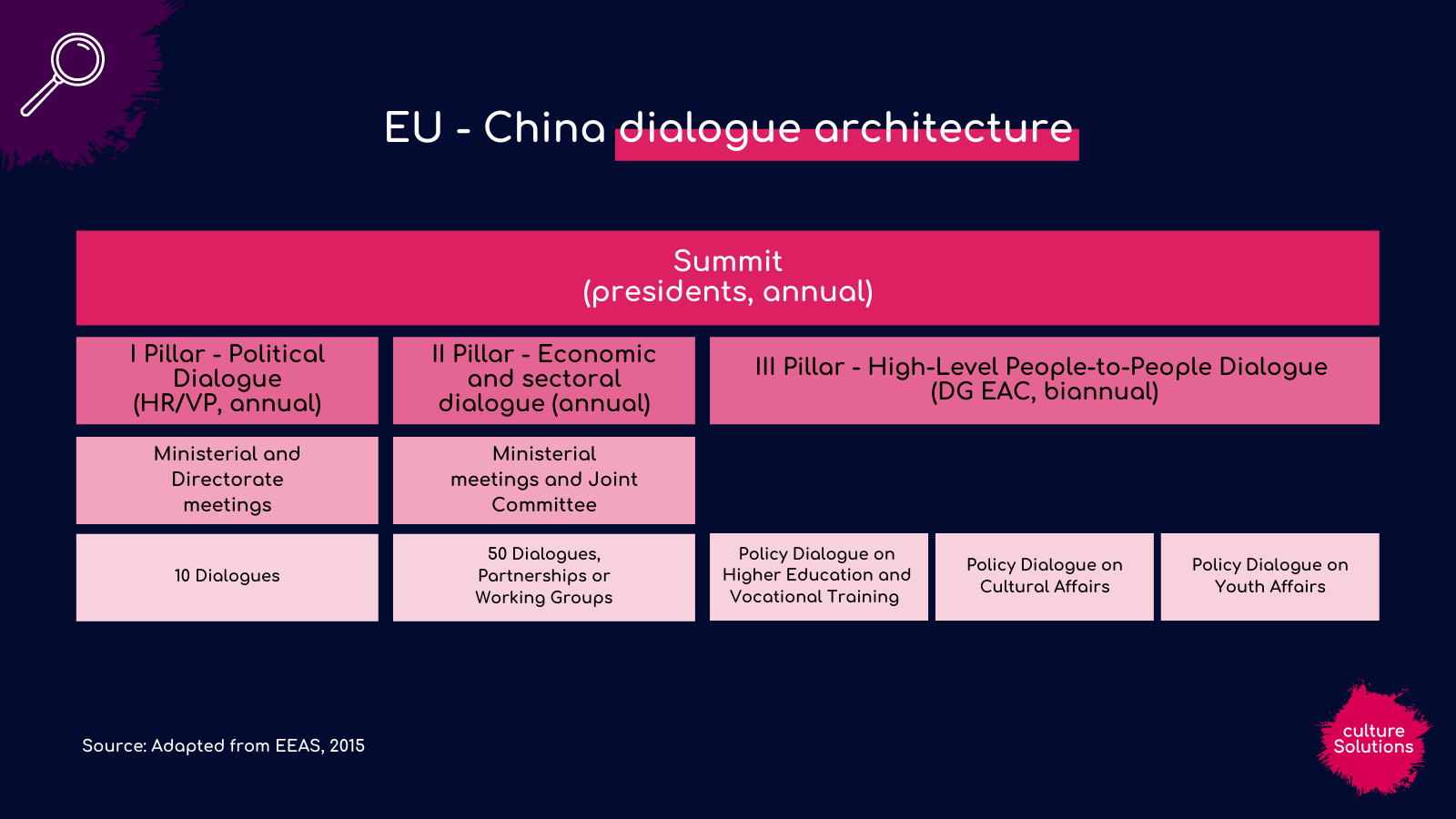

With political relations between the European Union and China at an all-times low, culture offers a safe space for collaboration between the two ever more geopolitical actors. The cultural pillar of the bilateral relation was established in 2012 under the title People-to-People Dialogue, and the following year it was described as a “cross-fertilisation between societies” in the EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation. However, with only three expert-level dialogues, none at the ministerial level and a biannual high-level meeting (rather than an annual one), cultural cooperation is clearly less prominent than the political and economic pillars with their more than 60 dialogues.

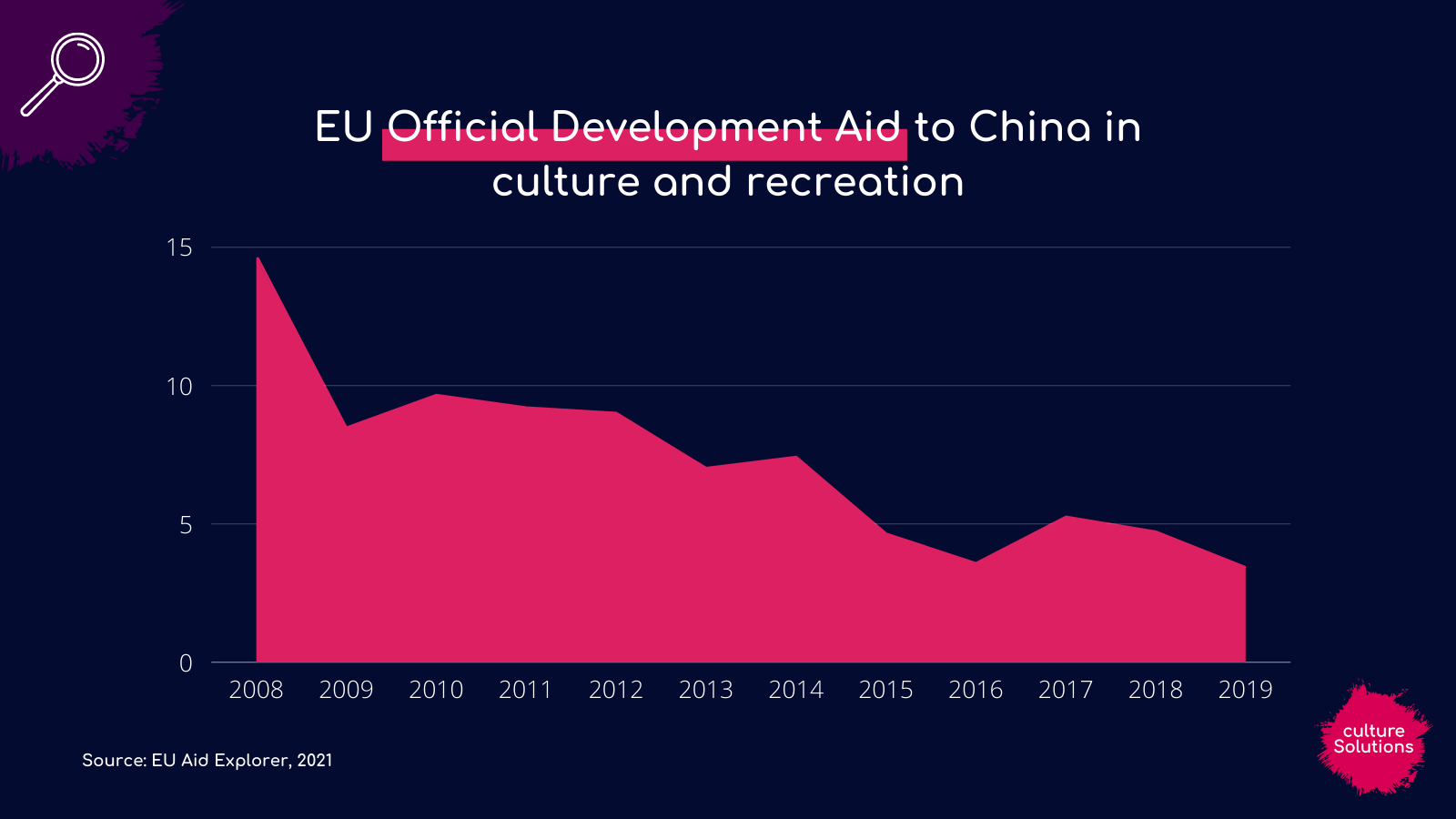

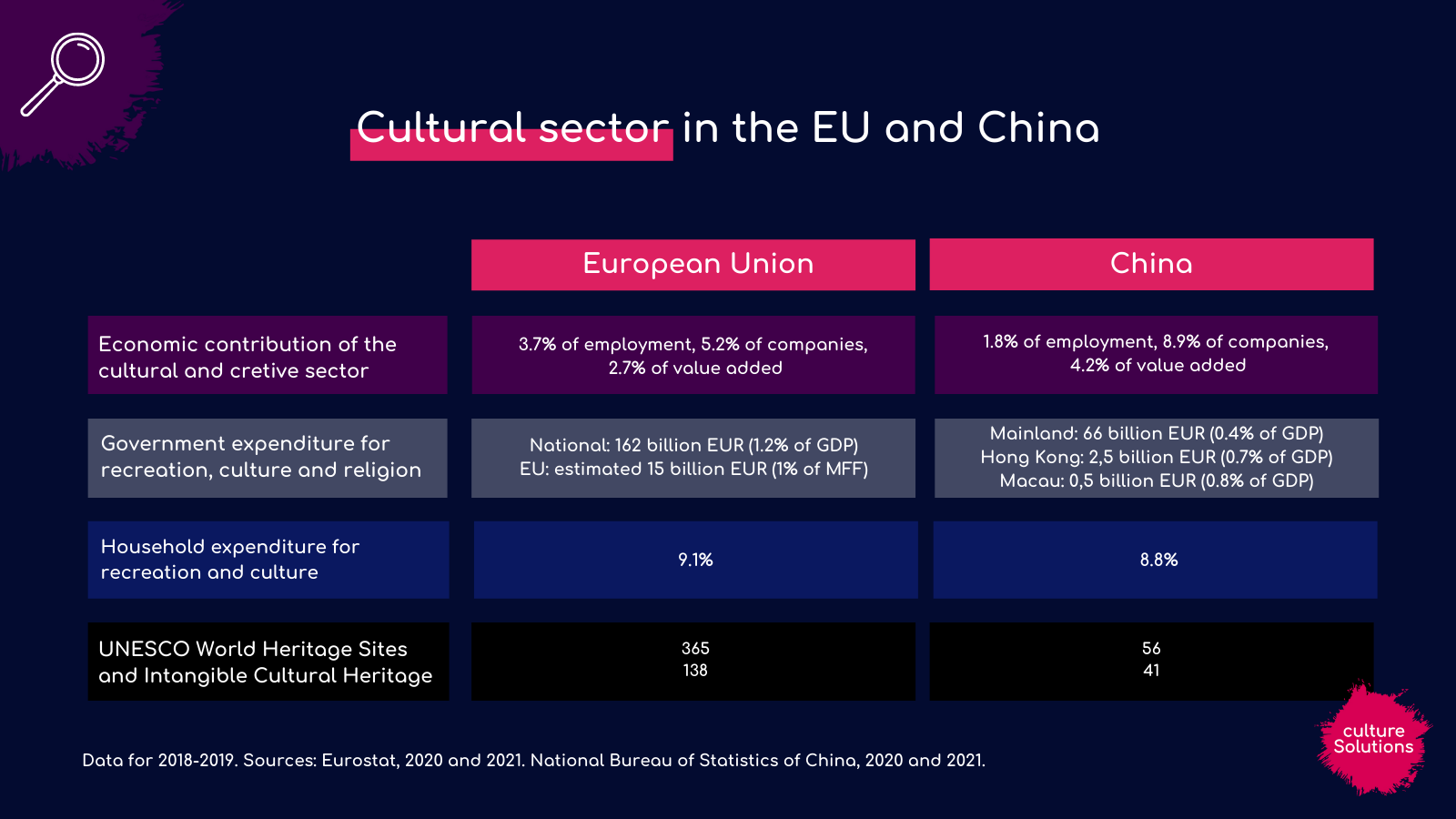

A certain momentum was built between 2012, designated EU-China Year of Intercultural Dialogue, and the publication of the 2016 Joint Communication “Towards an EU strategy for international cultural relations”: several joint studies and mappings were conducted, and the 40th anniversary of the official diplomatic relations took place. The areas most conducive to cooperation are protection of cultural heritage, cultural and creative industries and higher education owing to the alignment of interests. Furthermore, tourism is a top priority, as shown by the 2018 EU-China Year of Tourism.

Nevertheless, since then culture has been bogged down in increasing political tensions, especially in the areas of Human Rights and digital.

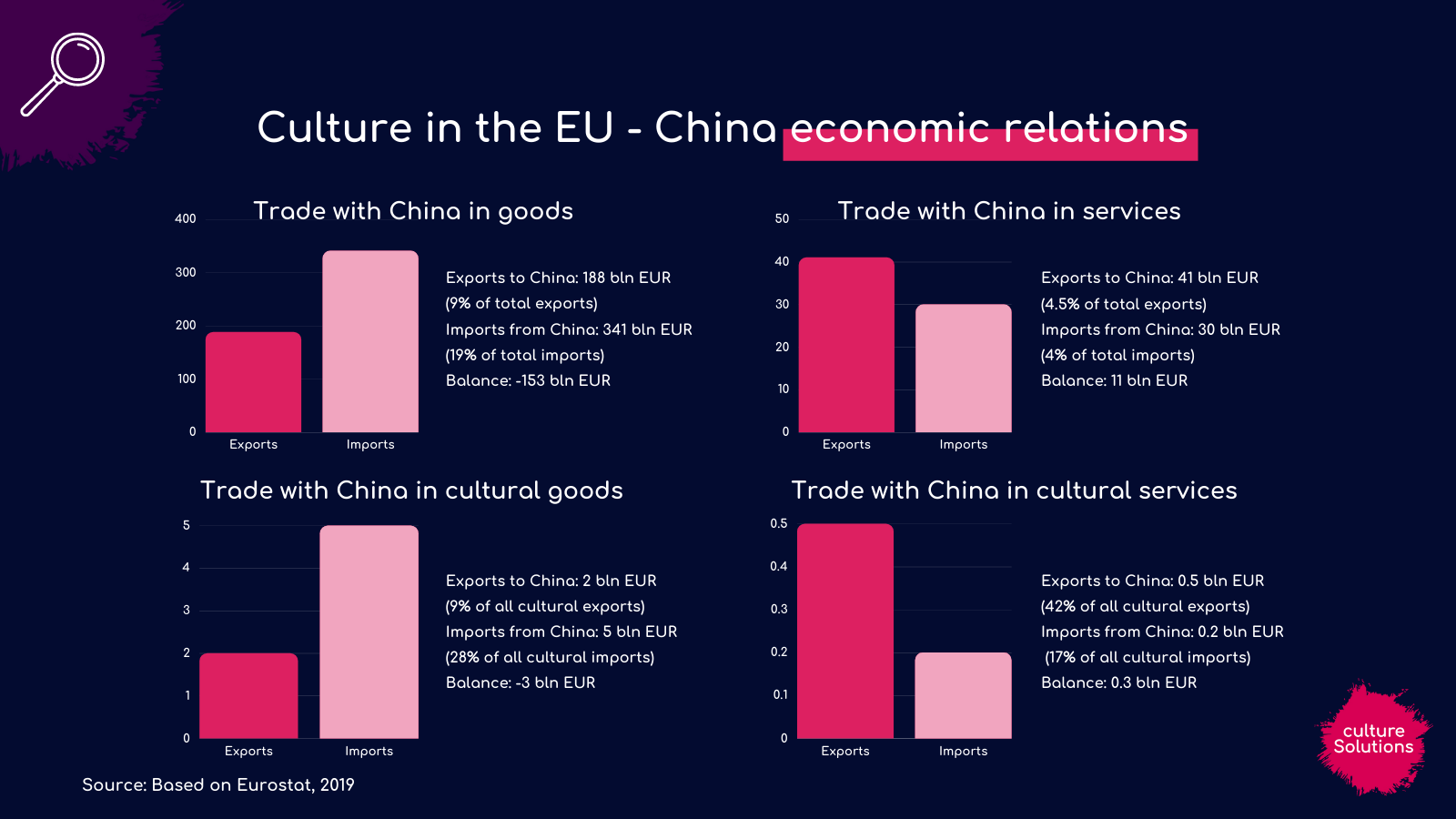

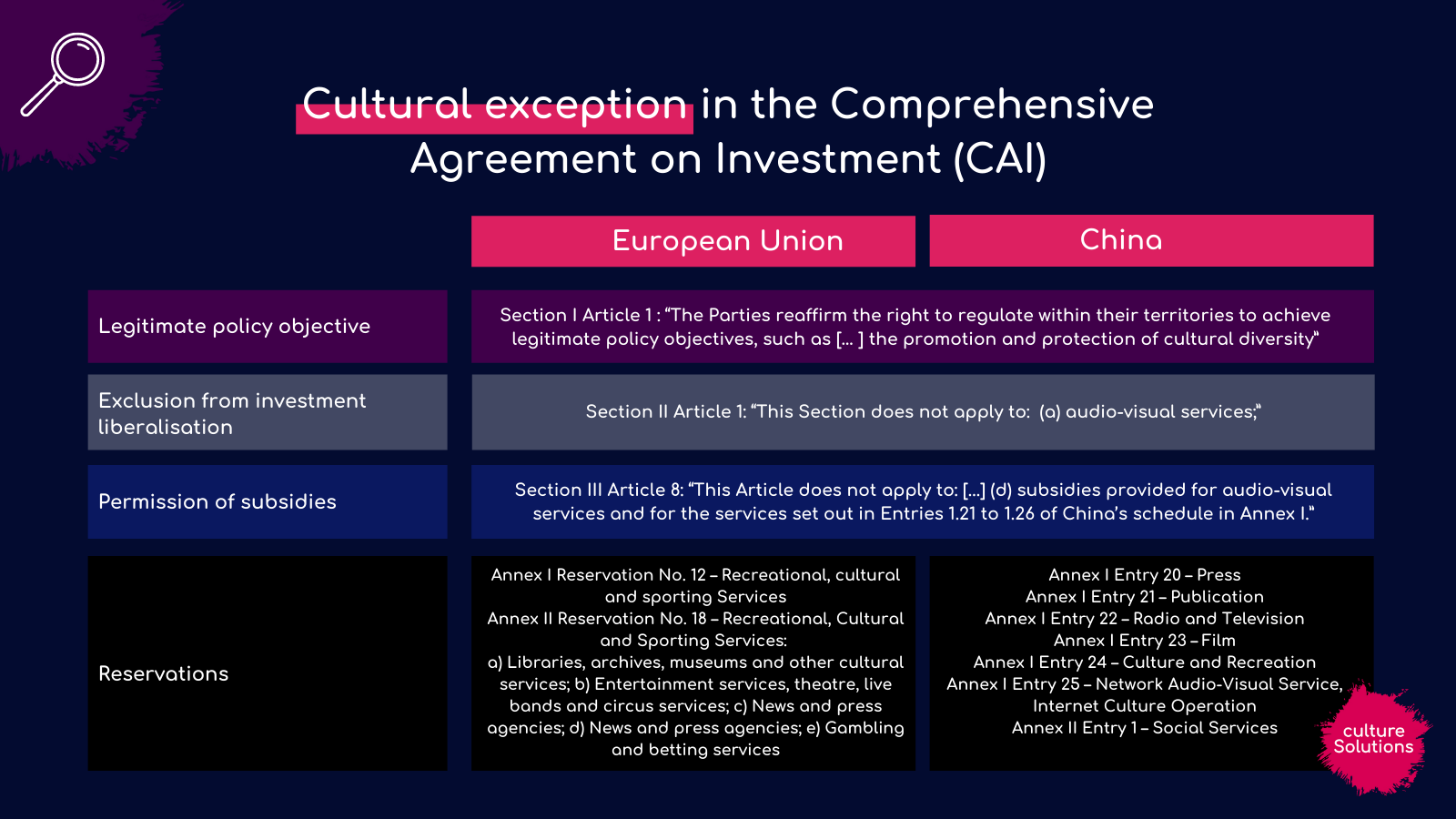

One example of this is the freezing of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). Since both the EU and China are parties to the 2005 UNESCO Convention on the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, CAI features a “cultural exception” for goods and services [1], which represent around 30%-40% of all cultural imports and exports of the EU. On the other hand, the reduced scale of the recent Winter Olympics ceremonies, as compared to the 2008 Summer Olympic Games, point to the changing priorities for Chinese Soft Power.

Comparing Chinese and EU cultural diplomacy systems

The 2019 strategy document “EU-China – A strategic outlook”, describes the Asian giant as a partner, a competitor, and a rival, and all three labels are applicable to the different aspects of the cultural relations between the two. Although the EU has produced several reports on China, including a 2012 Commission-EEAS Expert group and the 2014 Parliament Preparatory Action leading to the 2016 Joint Communication, these did not result in the adoption of a specific strategy on cultural relations with China, as advised by the 2019 Council conclusions.

On the ground, European cultural action is significantly impaired by the limited budget for culture: the only available funding comes under the public diplomacy line of the Partnership Instrument, and the EU Delegation in Beijing was stripped off its cultural focal point [2]. Moreover, EUNIC’s actorness is hindered by the Chinese government’s refusal to consider it an official counterpart [3], despite the publication of the 2011 Europe-China cultural compass. Additional challenges stem from the lack of awareness of the EU among Chinese citizens, their growing negative public opinion towards the rest and increasing nationalism.

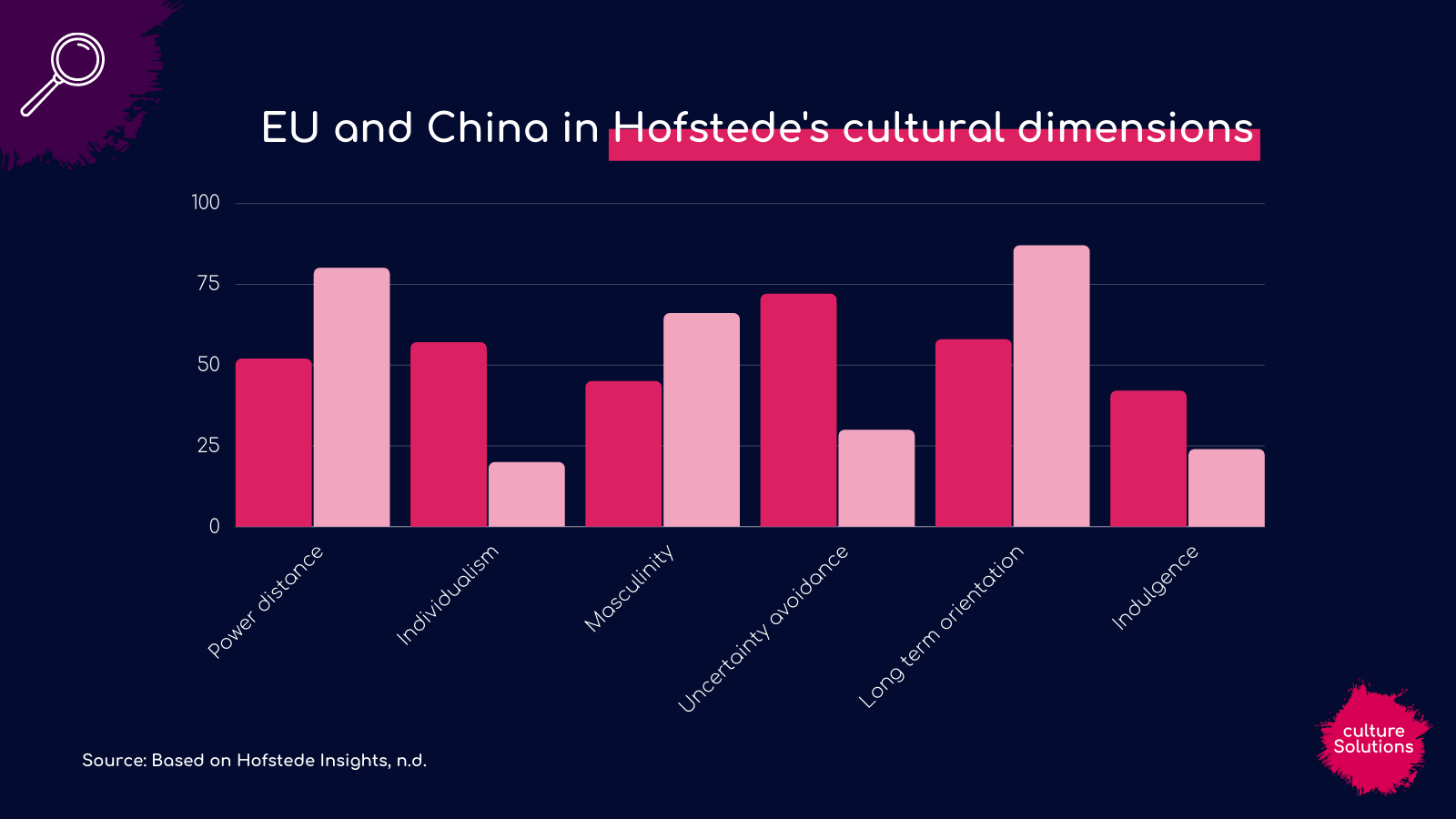

China’s approach to culture in external relations, called Cultural Soft Power, differs substantially from the European one: it is pragmatic, relies on the state, and thus is often perceived as a propaganda tool by other states.

Even though the ancient Chinese civilisation is particularly attractive to Europeans for its exoticism and thus contributes to the position of “cultural juggernaut” in Soft Power rankings, China opts for projecting a simplified and standardised image over its actual diversity [4]. Chinese policy papers depict culture as both a differentiator from the EU and an area of cooperation.

The principal actors of the Chinese Cultural Diplomacy are the Confucius Institutes, one in Brussels being specifically designated to the European Union. However, following a massive outcry, a damage control led to Hanban being rebranded as Centre for Language Education and Cooperation. Far less known (and impactful) are the China Cultural Centres Abroad – only 36 while Confucius Institutes surpass 500. The fact that Chinese embassies in Member States have a Culture and Education department gives it an edge over the European Union whose sole Delegation in Beijing is incapable of reaching out to the 1.4 billion population.

Mitigating differences, seizing opportunities: the way forward

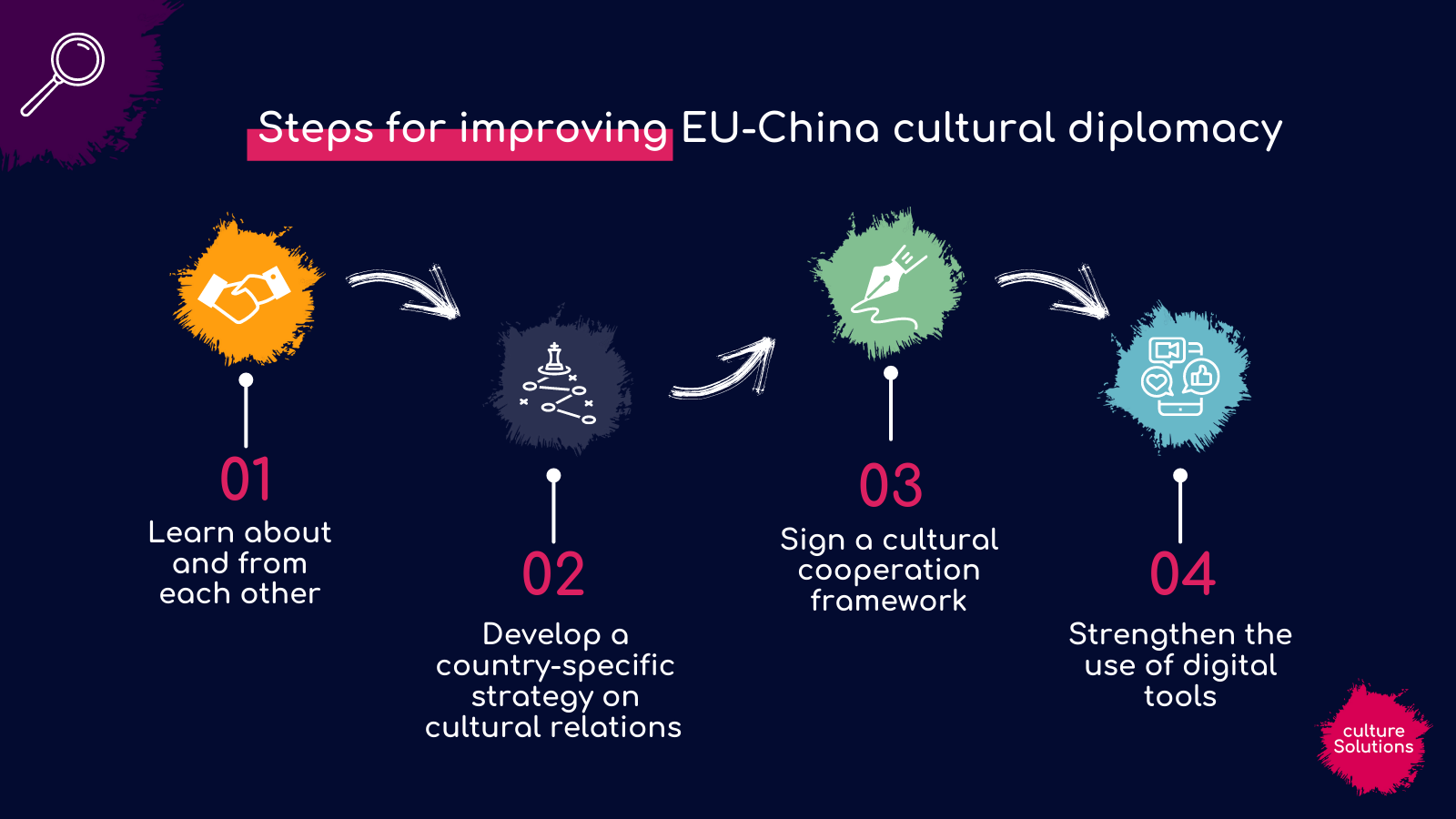

In the midst of COVID-19 induced border closures and deteriorating mutual perceptions [5], re-establishing trust between the EU and China is a prerequisite for stabilising their relations and negotiating the way forward, and the upcoming virtual summit on the 1st of April is a promising development after several delays. To reach the necessary level of convergence, it is imperative to reclaim the place of culture at the heart of Sino-European engagement through:

- Learning about and from each other: abandoning age-old rhetoric in favour of actively listening to the other part and replicating its strengths, cooperating with local partners (see the newly-launched European Space of Culture), and developing language and intercultural skills both among the general public and diplomats (by establishing a EU-China Culture Year and expanding Erasmus+ opportunities);

- Developing a country-specific EU strategy on cultural relations with China: putting away competition among EU Member States themselves and recognising the strategic importance of the “Middle State” would result in increased funding opportunities and common actions coordinated by the EU Delegation and the EUNIC clusters, allowing for increased credibility and sustainability of the projects;

- Signing a cultural cooperation framework: be it as an annex to the CAI or as a separate legal document with the purpose of promoting cultural diversity and specific joint projects, capitalising on the previous mapping and research phase; and

- Strengthening the use of digital tools: to reach citizens beyond Beijing and Brussels in an interactive way (for instance, exploring the Team Europe approach of the EU Global Gateway), while also boosting the potential for peer-to-peer exchanges and fair business-to-business cooperation rather than competition (in line with the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act).

Ultimately, for the EU-China cooperation to be effective in the long run, it should entail dealing with values in an open and respectful manner, by grounding their relations on the “united in diversity” principle [6] and embracing differences as a source of creative inspiration for a mutually beneficial guanxi.

This blog post is based on Ina Kokinova’s Bachelor’s thesis published in June 2021 by Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. While this article focused on cultural diplomacy between the EU and China, more research is needed on cultural relations at both the Union and the Member States levels.

The views expressed in this article are personal and are not the official position of culture Solutions as an organisation.

Notes and references:

[1] culture Solutions. (2021). Culture in EU external trade relationships: Towards Stronger Digital Cultural Cooperation. https://www.culturesolutions.eu/publications/culture-in-eu-external-trade-digital-cooperation/

[2] Information collected from an interview with a European diplomat.

[3] Smits, Y. and Raj, Y. (2014). Country report China. Preparatory Action ‘Culture in the EU’s External Relations’. https://www.cultureinexternalrelations.eu/cier-data/uploads/2016/08/China_report51.pdf

[4] Cappelletti, S. (2016). Chinese cultural diplomacy in the European context: between sophistication and lack of self-confidence. EU-China Observer, Vol. 4, Num. 16. https://www.coleurope.eu/system/tdf/uploads/page/eu-china_observer416_2.pdf

[5] The Service for Foreign Policy Instruments (FPI) is expected to publish a new edition of its 2015 Global EU perceptions study, which will provide useful insights into the impact of developments in recent years, such as trade tensions and COVID-19, and thus allow for comparison with the previous period characterised by stronger emphasis on EU-China cooperation.

[6] Expert Group On Culture And External Relations – China. (2012). United in diversity. Culture in the EU’s external relations: A strategy for EU-China cultural relations. https://www.cultureinexternalrelations.eu/cier-data/uploads/2016/11/Expert-group-Culture-and-Ext-Rel-China-Final-Report.pdf

Photo credits: Målning, Bildkonst, Painting. Huang Shan. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. CC BY.